Hindus, for instance, will argue that the lingam has nothing whatsoever to do with the male sexual organ, an assertion blatantly contradicted by the material. On each of these occasions, Sivas wrath was appeased when gods and humans promised to worship his lingam forever after, which, in India they still do. The lingam appeared, separate from the body of Siva, on several occasions. Wendy Doniger, an American scholar of the history of religions, states:įor Hindus, the phallus in the background, the archetype (if I may use the word in its Eliadean, indeed Bastianian, and non- Jungian sense) of which their own penises are manifestations, is the phallus (called the lingam) of the god Siva, who inherits much of the mythology of Indra (O'Flaherty, 1973). The Britannica encyclopedia entry on lingam also notes that the lingam is not considered to be a phallic symbol

The novelist Christopher Isherwood also addresses the interpretation of the linga as a sex symbol.

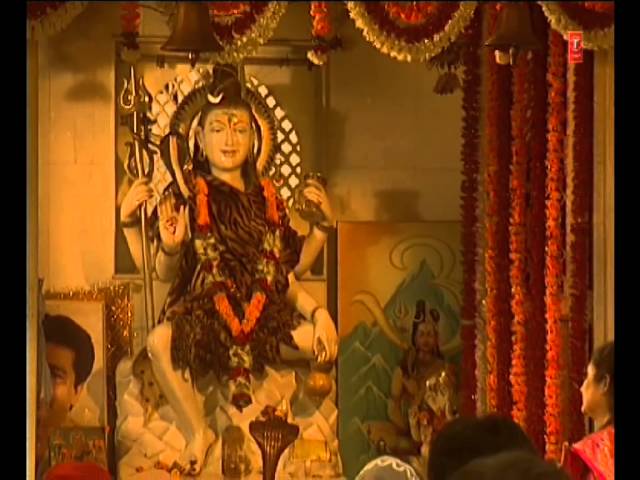

Īccording to Swami Sivananda, the view that the Shiva Lingam represents the phallus is a mistake The same sentiments have also been expressed by H. Vivekananda argued that the explanation of the Shiva-Linga as a phallic emblem was brought forward by the most thoughtless, and was forthcoming in India in her most degraded times, those of the downfall of Buddhism. According to Vivekananda, the explanation of the Shalagrama-Shila as a phallic emblem was an imaginary invention. This was in response to a paper read by Gustav Oppert, a German Orientalist, who traced the origin of the Shalagrama-Shila and the Shiva-Linga to phallicism. At the Paris Congress of the History of Religions in 1900, Ramakrishna's follower Swami Vivekananda argued that the Shiva-Linga had its origin in the idea of the Yupa- Stambha or Skambha-the sacrificial post, idealized in Vedic ritual as the symbol of the Eternal Brahman. Ramakrishna practiced Jivanta-linga-puja, or "worship of the living lingam". Narayan distinguishes the Siva-linga from anthropomorphic representations of Siva, and notes its absence from Vedic literature, and its interpretation as a phallus in Tantric sources. Ramachandra Bhatt, believe the phallic interpretation to be a later addition. Monier Williams wrote in Brahmanism and Hinduism that the symbol of linga, is "never in the mind of a Saiva (or Shiva-worshipper) connected with indecent ideas, nor with sexual love." According to Jeaneane Fowler, the linga is "a phallic symbol which represents the potent energy which is manifest in the cosmos." Some scholars, such as David James Smith, believe that throughout its history the lingam has represented the phallus others, such as N. ġ008 Lingas carved on a rock surface at the shore of the river Tungabhadra, Hampi, India Modern periodBritish missionary William Ward criticized the worship of the lingam (along with virtually all other Indian religious rituals) in his influential 1815 book A View of the History, Literature, and Mythology of the Hindoos, calling it "the last state of degradation to which human nature can be driven", and stating that its symbolism was "too gross, even when refined as much as possible, to meet the public eye." According to Brian Pennington, Ward's book "became a centerpiece in the British construction of Hinduism and in the political and economic domination of the subcontinent." In 1825, however, Horace Hayman Wilson's work on the lingayat sect of South India attempted to refute popular British notions that the lingam graphically represented a human organ and that it aroused erotic emotions in its devotees. In the Linga Purâna the same hymn is expanded in the shape of stories, meant to establish the glory of the great Stambha and the supreme nature of Mahâdeva (the Great God, Shiva). The Yupa-Skambha gave place in time to the Shiva-Linga. As afterwards the Yajna (sacrificial) fire, its smoke, ashes and flames, the Soma plant and the ox that used to carry on its back the wood for the Vedic sacrifice gave place to the conceptions of the brightness of Shiva's body, his tawny matted-hair, his blue throat and the riding on the bull of the Shiva. In that hymn a description is found of the beginningless and endless Stambha or Skambha and it is shown that the said Skambha is put in place of the eternal Brahman. Some associate Shiva-Linga with this Yupa-Stambha, the sacrificial post.

There is a hymn in the Atharvaveda which praises a pillar (Skt: Stambha), and this is one possible origin of linga-worship. Some believe that linga-worship was a feature of indigenous Indian religion. Wat Pho lingamAnthropologist Christopher John Fuller notes that although most sculpted images ( murtis) are anthromorphic, the aniconic Shiva Linga is an important exception.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)